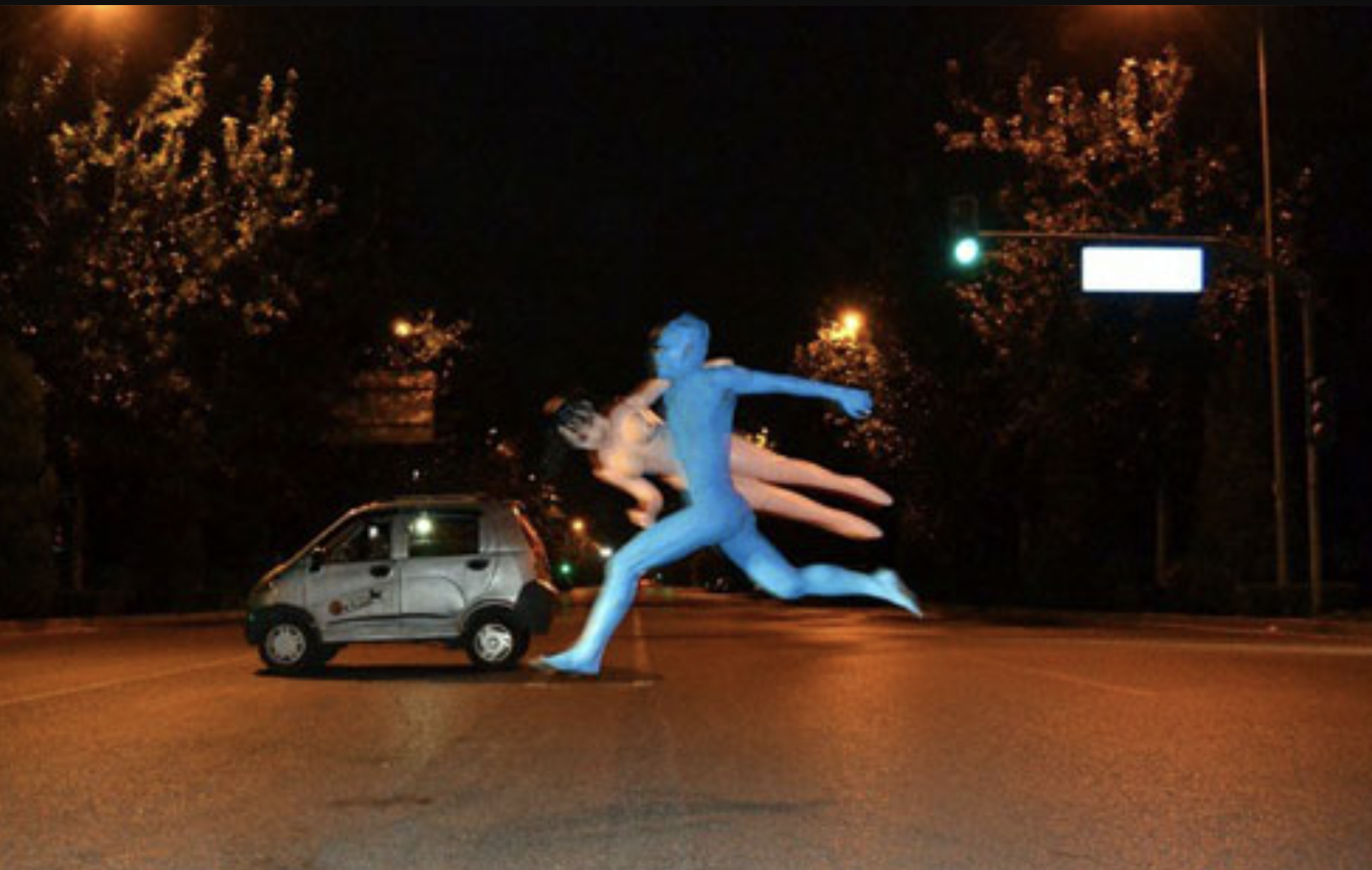

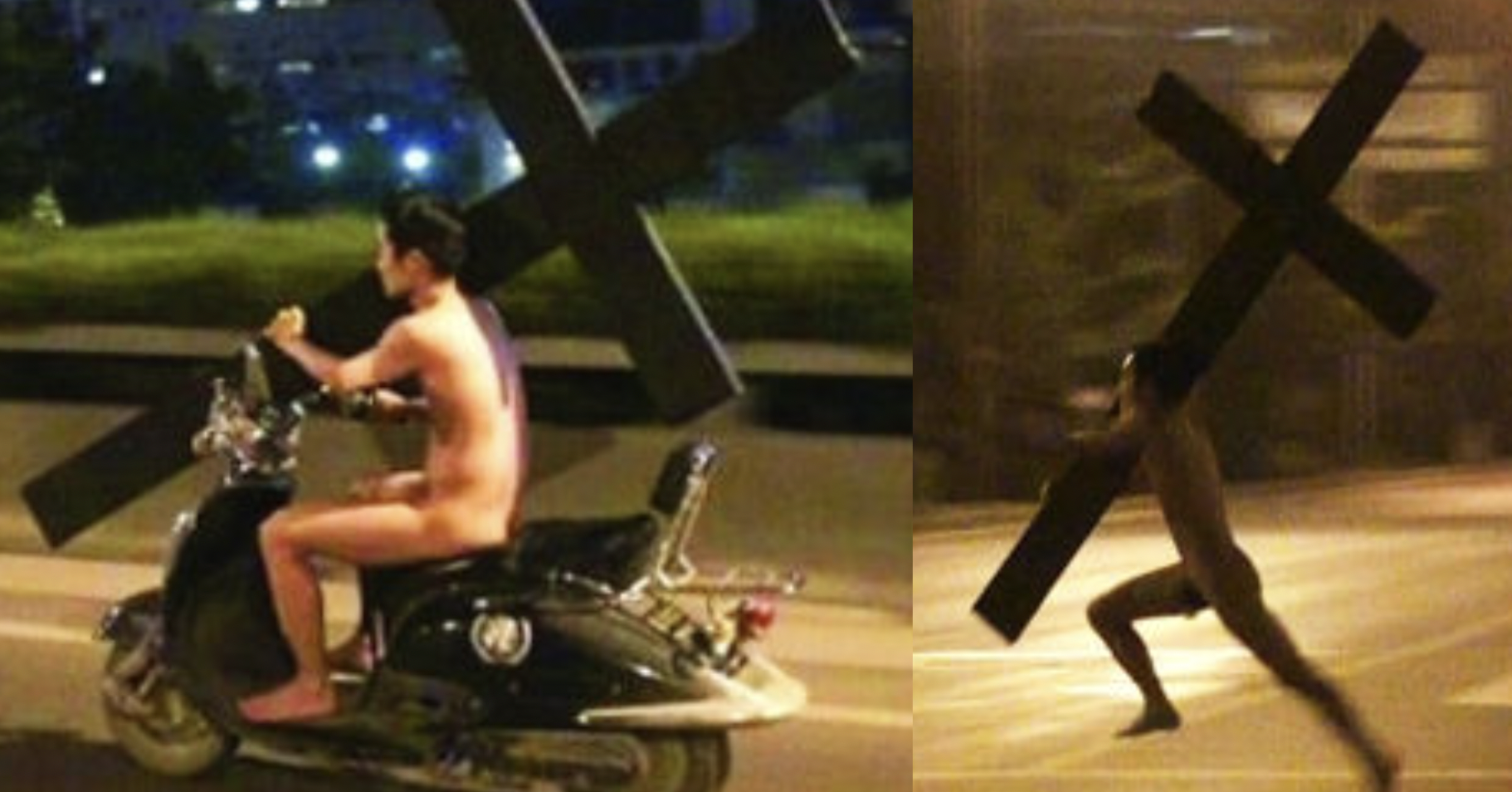

In early Spring 2013, a naked man with his body covered head-to-toe in blue paint was spotted running through the quiet late-night streets of Beijing. Sometimes seen riding a motorcycle while carrying a wooden cross twice his height; other times sprinting around clutching an inflatable sex doll under one arm. The bizarre spectacle quickly went viral online, with netizens dubbing the him “Brother Streaking.”

The man later revealed himself as Li Binyuan, a graduate of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, China’s most prestigious art school. Li told People’s Daily that he often experienced creative blocks, and streaking was a good way to release that pressure. “We live in boring and oppressive times,” he said. “What I did in itself was just a casual act. It ended when I’d had enough.”

In an interview with NetEase, when asked why he carried objects while streaking, Li replied: “Because it’s interesting. It’s quite beautiful, an ethereal kind of beauty that is magical and absurd. Just like reality.”

On a crowded subway during rush hour, Li was photographed brushing his teeth and shaving, bringing private routines into a communal space. One night in Beijing, he strapped kitchen knives on his feet, blade side down, and sped off on his motorcycle, with the friction sparking fire behind his feet. In another instance, he shot fireworks at a sewage dump and named the piece, Spring of Sewage (臭水沟的春天).

Many of Li’s works juxtapose absurdism with the mundane. His humor and offbeat charm would define his career, as he sought not only to understand the world but also to force it to understand him. He is constantly trying to tear through the fabric of reality and shout the message of: I have free will — watch what I can do!

Born in 1985 to a modest farming family in Southern China’s Yongzhou city in the Hubei Province, Li graduated from art school in 2011 and opened his studio in Beijing. Though trained as a sculptor, Li rose to fame as a performance artist, with his work being exhibited across China, Europe, and the United States. Li’s early works carry the steel-gray melancholy of the urban north. By contrast, it is his hometown of Yongzhou (whose name poetically translates to “The Forever Prefecture”) that gives a warmth of color and intimacy to his artwork.

Freedom Farming (自由耕种), Li’s first hometown performance, saw him repeatedly hurling himself into mud until he vomited. The entire ordeal lasted over three hours, while curious villagers looked on. Li describes his relationship with his hometown as one of love and hate. As he threw himself onto the land once owned by his late father, he felt calm despite the violence of the act. Reflecting in a 2017 interview, he said:

“I long to be understood and accepted by this place. I yearn to communicate, but this kind of communication cannot be achieved through words, so I chose the most direct and instinctive way to have a conversation… In the end, I reached a reconciliation, and I was free.”

Li’s endeavour to sculpt with his body frequently puts him in danger. In Testing (测试), he climbed a bamboo tree outside his childhood home and clung to the swaying branch until he lost grip, plummeting onto concrete. The performance left him with a concussion and permanent back damage. His riskiest piece, 2cm, took place in the factory where his mother once worked, operating a massive industrial saw. With his mother controlling the machine, Li stood just two centimeters from the spinning wheel for three unflinching minutes.

Li’s father passed away when Li was 13, and the purpose of his artwork 2cm was to experience firsthand the risk his mother faced to support the family. His father, a security guard working in Guangdong Province, had sent home a letter shortly before dying in a freak accident at age 36. In 2020, when Li himself turned 36, he created The Last Letter (最后一封信). He divided his father’s words into 36 lines, dressed as a security guard, and traveled to Guangdong. There, he found 36 security guards and asked each of them to teach him a line in Cantonese. He then read the letter aloud in his own broken Cantonese, building a bridge between past and present, in search of his father’s voice across time.

Years later, Li called it his most meaningful project. “For me, it was something very concrete, something that had to be done, something that could explain who I am,” he states. It was no longer performative art; it was a performance for himself.

Through such projects, Li’s own body and mind became the raw material he carves, molds, and chips away at. Thus, lonely city streets and secluded hometown backyards became his only canvas. Li’s artwork undoubtedly carries a rebellious undercurrent, one that rejects the ordinariness of life. He often stages battles against nature, like in Torrent (洪流), where he swam against a current but remained fixed in place. Or Canvas 90×60 (画板90×60), where he held a canvas beneath a waterfall until his arms gave out. Nature is the immovable rock, and Li Binyuan strives to be the unstoppable force.

One of his longest-running works, Until the Bridge Collapses (直到桥梁坍塌), began in 2012. Each time he returns to the village, he does a cartwheel across the same bridge he crossed as a kid. He said the project will only end when the bridge collapses or when he can no longer do a cartwheel. If the bridge falls first, perhaps he will have proved his victory over nature, over the immovable rock.

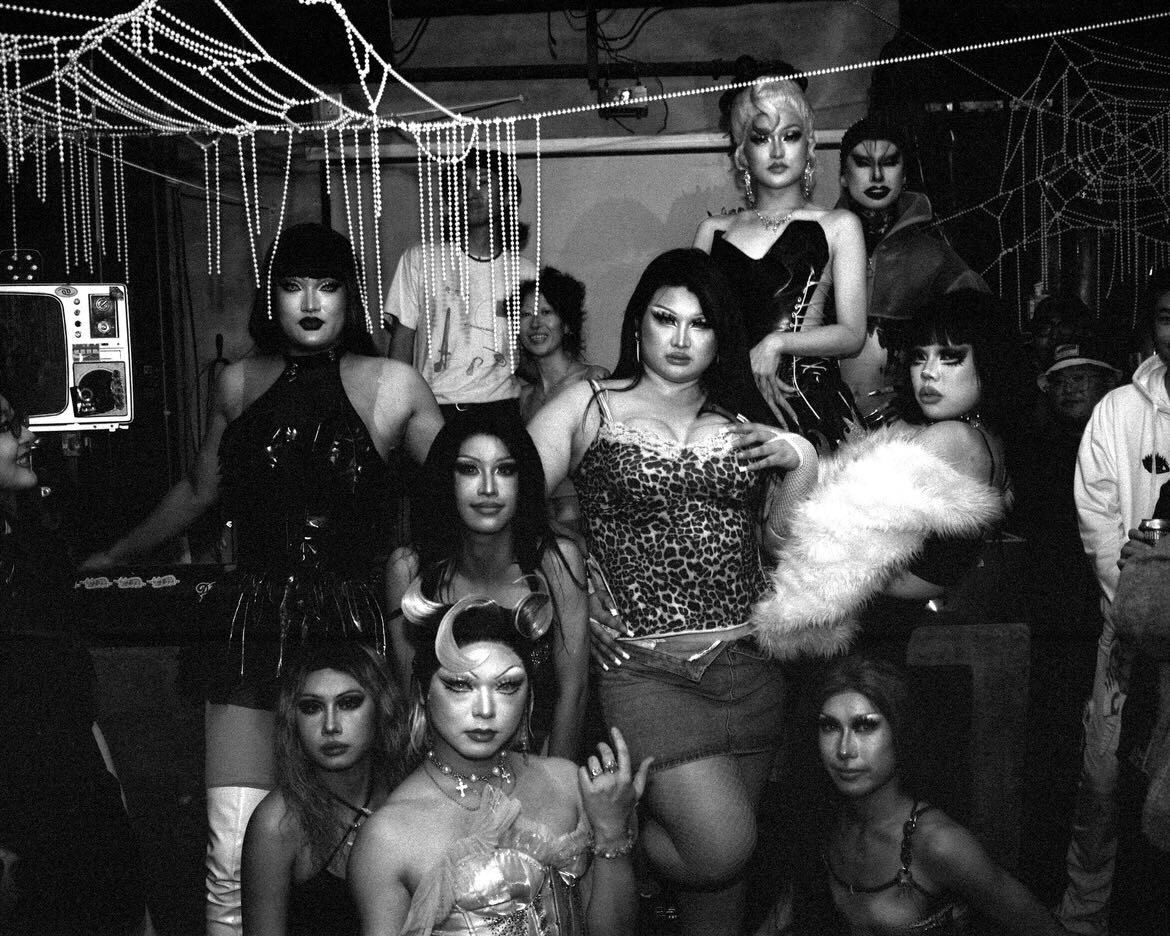

Cover image via Li Bingyuan